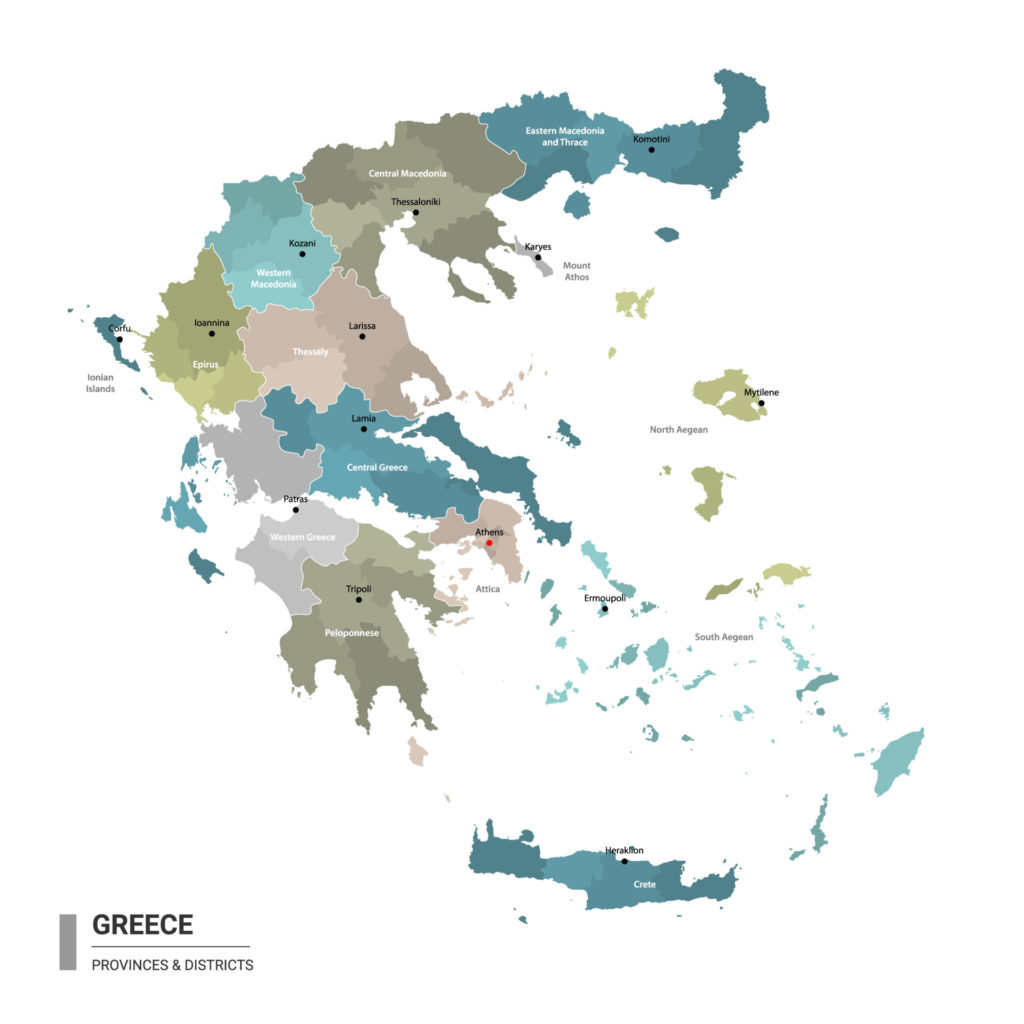

Cunda Island, also known as Alibey Island is the largest island in the Ayvalık Islands archipelago nestled off the northwestern coast of Turkey, near the town of Ayvalık in Balıkesir Province. This picturesque island, boasting a rich history and captivating beauty, lies approximately 16 kilometers east of the Greek island of Lesbos.

Unveiling the Untold Story of Cunda Island

Cunda Island, a captivating blend of history and natural beauty, holds a story often untold. This article delves into the island’s past, exploring its evolution from a thriving Greek community to a modern-day tourist destination.

A Glimpse into Cunda’s Past

Cunda Island’s history stretches back to antiquity with records mentioning settlements dating back to that era. The island was once home to a vibrant Greek community as evidenced by the numerous churches and other architectural remnants. However, the 20th century brought significant changes to Cunda’s landscape.

The 20th Century: A Time of Turmoil and Transformation

The early 20th century witnessed the forced displacement of the Greek population from Cunda, a consequence of the tumultuous events surrounding the Ottoman Empire’s decline This tragic event left an indelible mark on the island’s history, with abandoned churches and deserted homes standing as silent reminders of a lost community.

A New Chapter: Cunda’s Transformation into a Tourist Destination

Despite its turbulent past, Cunda Island has emerged as a popular tourist destination in modern times. Its charming stone houses, picturesque streets, and rich cultural heritage draw visitors from near and far. Today, Cunda offers a unique blend of history, natural beauty, and modern amenities, making it an ideal getaway for those seeking a relaxing and culturally enriching experience.

Exploring Cunda Island’s Highlights

Cunda Island offers a diverse array of attractions for visitors to explore. Some of the island’s must-see sights include:

- The Church of the Taxiarchs: This former Greek Orthodox cathedral, now a museum, stands as a testament to the island’s rich history.

- Poroselene Bay: This picturesque bay, renowned for its legend of a dolphin saving a drowning boy, offers stunning views and a tranquil atmosphere.

- The Houses of Cunda: The island’s charming stone houses, adorned with vibrant flowers and architectural details, are a sight to behold.

- Cunda’s Culinary Delights: From fresh seafood to traditional Turkish cuisine, Cunda offers a delectable array of culinary experiences.

A Journey Through Time and Beauty

Cunda Island is a destination that invites visitors to embark on a journey through time and beauty. Its rich history, captivating scenery, and warm hospitality make it an unforgettable experience. Whether you’re seeking a relaxing getaway or a cultural immersion, Cunda Island has something to offer everyone.

Additional Resources:

- Cunda Island on Wikipedia: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cunda_Island

- The Untold Story of Turkey’s Cunda Island on New Lines Magazine: https://newlinesmag.com/reportage/the-untold-story-of-turkeys-cunda-island/

Frequently Asked Questions:

- How do I get to Cunda Island?

Cunda Island is easily accessible by ferry or bus from the town of Ayvalık.

- What is the best time to visit Cunda Island?

Although the island is accessible all year round, the best seasons to visit are in the spring and fall.

- What are some of the things to do on Cunda Island?

Visitors can explore the island’s historical sites, relax on its beaches, indulge in its culinary delights, and enjoy its vibrant nightlife.

Additional Notes:

- Cunda Island is a popular tourist destination, so it’s recommended to book accommodations and transportation in advance, especially during peak season.

- The island offers a variety of accommodation options, ranging from budget-friendly guesthouses to luxurious hotels.

- Be sure to try the local cuisine, which includes fresh seafood, traditional Turkish dishes, and delicious desserts.

- Cunda Island is a great place to relax and unwind, but it also offers plenty of opportunities for adventure and exploration.

Turkey’s Cunda Island may be a popular tourist destination, but it’s also a casualty of post-Ottoman nation building Share

Cunda is the biggest of the 22 islands governed by Ayvalık, a north Aegean district in Turkey. It shares a layered history with its mainland, starting with its name. Governmental websites and Google Maps adamantly refer to it as “Alibey” after a Turkish lieutenant colonel. But because of its catchy name, the island is mostly known in Turkey as “Cunda,” avoiding the early republic’s popular attempt to Turkify place names. Meanwhile, its previous occupants, the Eastern Orthodox Christians of the Ottoman Empire, referred to it as “Moschonisi,” or the perfumed island.

As the Ottoman Empire gradually seized control of the empire’s territories, the term “Romios-Rum,” which had originally referred to subjects of the Eastern Roman Empire, eventually came to refer to Eastern Orthodox Christians. One of the non-Muslim communities of the Abrahamic religions under the millet system, which granted them autonomy in matters of law and religion, was the Greek-speaking “Rum millet.”

Particularly before nation-states were established, “Rumness” could not be entirely divorced from Greek identity due to the language and cultural sensitivities of the people. In modern Turkey, the word “Rum” unequivocally denotes the Greek-speaking, Christian minority in the country. After suffering through oppressive taxes, pogroms, and state-led expulsion in the 20th century, the community is barely surviving today. Their once-thriving businesses have collapsed, and their schools have closed due to a lack of students. The Rums are consistently one of the most frequently targeted groups in hate speech in Turkish media whenever political unrest breaks out in the Mediterranean. They are widely portrayed as the enemy. They are despised in their own nation, despite having lived in Anatolia for centuries before Turks arrived there in 1071—the Seljuk Turks, who seized much of the region following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071—calling their state the Rum Seljuk Sultanate.

On the island of Cunda, a lot of hotels and vacation rentals call their buildings “Rum,” sometimes combined with “stone,” as Turkish tourists easily associate these terms with elegance and a charming nod to the past. Even though there is no sign of the people who built and originally lived there, their foreignness is nonetheless secure, useful, and pleasurable. In fact, tourists are often drawn to the low-rise residences with their corbeled wrought iron balconies, almond green, rose, and blue shutters adorned with bursts of bougainvillea, and dusty pink sarımsak taşı, a local volcanic stone. Some of these houses are private dwellings, some are boutique hotels.

The main historical landmark and postcard material on the island is the restored Church of the Taxiarchs, which is now a museum filled with antiques like model ships, tiny tea sets, and alarm clocks gathered and displayed by one of the wealthiest families in Turkey.

Before Rahmi M. When Koç Museums restored the church in 2014, it had deep cracks on its apse, hollowed-out arch windows, and other signs of decay. The island’s standing churches have been stripped of their original purpose. The third and oldest church was abandoned and reduced to a dilapidated shell, but the same family preserved another and used it as a library. The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople claims that approximately 6,000 people left Rum in the early 20th century. Those who created the island’s touristic appeal today were replaced by Muslims who came from Crete and Mytilene. Cunda’s current locals are their descendants.

A deeper examination of Cunda and Ayvalık’s past necessitates an unlearning process for most Turkish citizens, who were raised under a dense cloud of nation-building myths that flatly deny or minimize the devastation and slaughter carried out by our fellow Turks in the first part of the 20th century.

Many educated in Turkey’s state education system would attribute the current ethnic composition of Cunda and nearby Ayvalık, as well as the silent remains of their ancestry, to the Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923.

Though they are still up for debate due to competition over natural resources, the borders between the two countries were established by the Treaty of Lausanne and, along with the widespread expulsion of people from their ancestral homelands, led to the largely homogenized ethnic compositions of Greece and Turkey today. The exchange, which historian Çağlar Keyder referred to as “a civilized version of ethnic cleansing” and one of the epilogues to the long age of empires, resulted in the displacement of about 400,000 Muslims in Greece and nearly one million others. 2 million Rums in Turkey.

What bureaucrats thought was a cunning scheme to help both countries promote their respective nationalist narratives turned out to be anything but that. According to Bruce Clark’s book “Twice A Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey,” immigrants from Anatolia were referred to as yarı gavur (half infidel) when they were Muslims from Crete and Tourkosporoi (seeds of Turks) when they first arrived in Greece. Until the ends of their lives, thousands of families pined for the lands they were forced to leave.

These days, visitors to Cunda can buy locally produced olive oil, taste the delicious lor cheese that is produced on the island the same day, have a bowl of syrupy fried lokma on the pier, and indulge in some of the best Cretan specialties, like warm saganaki cheese, stuffed zucchini flowers, and prawns cooked in thyme. Taş Kahve is a spacious coffee shop on the pier with tall windows tinted on the arches, perfect for accommodating both tourists and middle-aged local men who are eager to tick off things on their bucket list while visiting Cunda. The fact that this building, formerly known as Kafeneion O Ermis (Hermes Café), was deserted and vandalized a long time before the Lausanne Treaty was signed is conspicuously absent from Turkey’s official historiography.

Millions of Turkish adults still remember the chilling phrase “Yunanlıları denize döktük” (literally, “We poured Greeks into the sea”), which describes our victory on the Aegean coast in the War of Independence. I do not recall a feeling of pity, shock, or sympathy but a sense of vindication. Invading soldiers should not have stepped onto our soil in the first place. The Greek army had killed our helpless fellow citizens, the Turks, and they ought to have been expelled from the country together with their allies from Rum.

Such graphic statements carve a deep, if not indelible, place in the minds of children. At an impressionable age, things that are easily dismissed become ingrained beliefs unless they are later personally challenged. To this day, around Sept. The exact words from that proclamation, which honors İzmir’s independence in 1922 and praises Kemal Atatürk’s army for having “poured” the enemy into the sea, are repeated in newspapers.

In Cunda, September 1922 was a fateful month for many Rums. According to information provided by Clark in his book, only a small portion of the several hundred civilians, spanning all ages, were spared and placed in orphanages. Regarding the pre-exchange days of the island, the author wrote in a recent correspondence: “On September 14, 1922, it is said that the local bishop, Ambrosios, was buried alive.” ” According to another local tradition [sic], several hundred islanders were killed on September 19th. ”.

I first went to Cunda in summer 2020. As my friends who had visited the island before me had told me, I returned from my trip with the aftertaste of a wonderful, restful vacation. I had always been interested in the history of the island, but until I read Clark’s “Twice A Stranger,” I knew very little about it. Several thousand people lived in Cunda, according to Clark’s description in our correspondence, all of whom were Greek in terms of language, religion, and consciousness. “The primary industries were fishing, sponge diving, and boatbuilding, for which the island was well-known,” he went on. ” .

They paid the price for being in the wrong location across the Aegean at the wrong time, when the Ottoman Empire was trying to survive by sacrificing its own people.

Looting, destruction, and murder in the early 20th century completely turned life in Cunda and on the Ayvalık mainland upside down. According to Patriarchate records, there have been instances of theft and looting in Ayvalık since the beginning of the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), when the locals were forced to leave their homes due to growing persecution. Churches were turned into stables and warehouses when they left Cunda; paintings were destroyed, lamps and holy items were broken, and houses were left unusable. According to Clark, in 1915, the islanders who had made it out were forced to pay a heavy tax to pay for the uniforms and accommodations of the Ottoman military. They paid the price for being in the wrong location across the Aegean at the wrong time, when the Ottoman Empire was trying to survive by sacrificing its own people.

The graphic novel “Aivali: A Story of Greeks and Turks in 1922” by Greek caricaturist SoloÍp narrates the experiences of Greeks and Turks who endured hardships during the population exchange. It features tales from four different authors, as well as striking depictions of actual events and eerie mental images, all complemented by a wealth of testimonies that Soloúp found motivational. Beyond violent incidents on both sides, the book disproves the demonization of the “other” in Greek and Turkish identities by telling stories of friendship, romance, and serendipitous encounters that evoke compassion.

Soloúp’s grandparents were born in İzmir. His grandmother Maria was one of the many people caught in the great fire of İzmir shortly after the Turkish army entered the city and declared its independence in September 1922. Maria, hopelessly fleeing from rape, threw herself into the sea to commit suicide. She swam among dead bodies before being saved by an American ship. Like thousands of Rums who were trying to survive the fire, Maria wasn’t an invader. She was more Anatolian than millions of us in Turkey today can claim to be.

One panel that sticks in the mind when reading “Aivali” is the one where a priest screams at fellow islanders on boats escaping to neighboring Mytilene from invading Turks, hinting at the whirlwind of faith, disbelief, and hope that Cunda’s residents must have felt in 1922. He tells them that Cunda is their homeland and that they will be able to coexist peacefully with the Turks there once more. Later in the book, a Turkish man with roots in Crete talks about what his ancestors discovered when they arrived in Cunda. Most houses had traces of massacres with stains of dried blood and corpses in wells. What they saw was more a sign of sudden, desperate exodus than a programmed expulsion. According to Renée Hirschon’s book “Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey,” the following describes the scene: “When we first arrived in Moschonisi, we were surprised to find that on the tables were dishes of food, some of it already on forks ready to be eaten.” ” ”.

“Aivali” narrates the tale of renowned Greek writer Elias Venezis, who was one of the roughly 3,000 Rum men in Ayvalık who were forcibly transported to Ottoman labor battalions between the ages of 18 and 45, where they faced enslavement, torture, and death. According to historian Speros Vryonis Jr. For the most part, those thousands of Greeks in the slave labor camps lacked an official identity. They could (be made to) disappear quietly and without any fanfare. ” Venezis, who was 18 at the time of his forced conscription, was one of only 23 survivors.

The population exchange engineers set out to create two new nations out of the suffering of one nineteen eighteen years ago. 6 million souls. The stories left behind were erased by political will or the practical needs of those compelled to live in strange houses. The population exchange, combined with the government’s ethnocentric rhetoric and policies, leaves a lasting impression on the collective consciousness of many Turkish citizens in the midst of the country’s current climate of tolerated growing Hellenophobia.

A trip to Cunda these days can begin and end with only scraps of knowledge diluted with omissions. “Just like Ayvalık, Cunda is unthinkable without the sea. “The stories of people and buildings begin with and end in the sea,” reads a town brochure distributed by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, referring to a former orphanage that is located along the island’s shore. The stories of many of its citizens do end in those waters because they ran for their lives and never returned.