Wherever plants or animals are domesticated and farmed, diseases and parasites are sure to be found. Parasites that live on freshwater aquarium shrimp are becoming more common. This is likely because many species, especially those in the genus Neocaridina, are being raised for commercial purposes. The most common external parasites are found on the animals’ surfaces and appendages. In the wild, these infestations probably don’t kill fish very often, but in aquaculture ponds and tanks with a lot of fish, they can get out of hand and make it hard for fish to move, molt, grow, and do their job. Breeding and feeding may stop, and mortality may result. High infestation of the gills, as found with peritrich ciliates, can affect respiration and may be fatal. Since parasites can easily be passed from one species to another, it is important to treat any animals that are sick right away, keep new shrimp in a quarantine area, and maybe give all new animals a welcome dip.

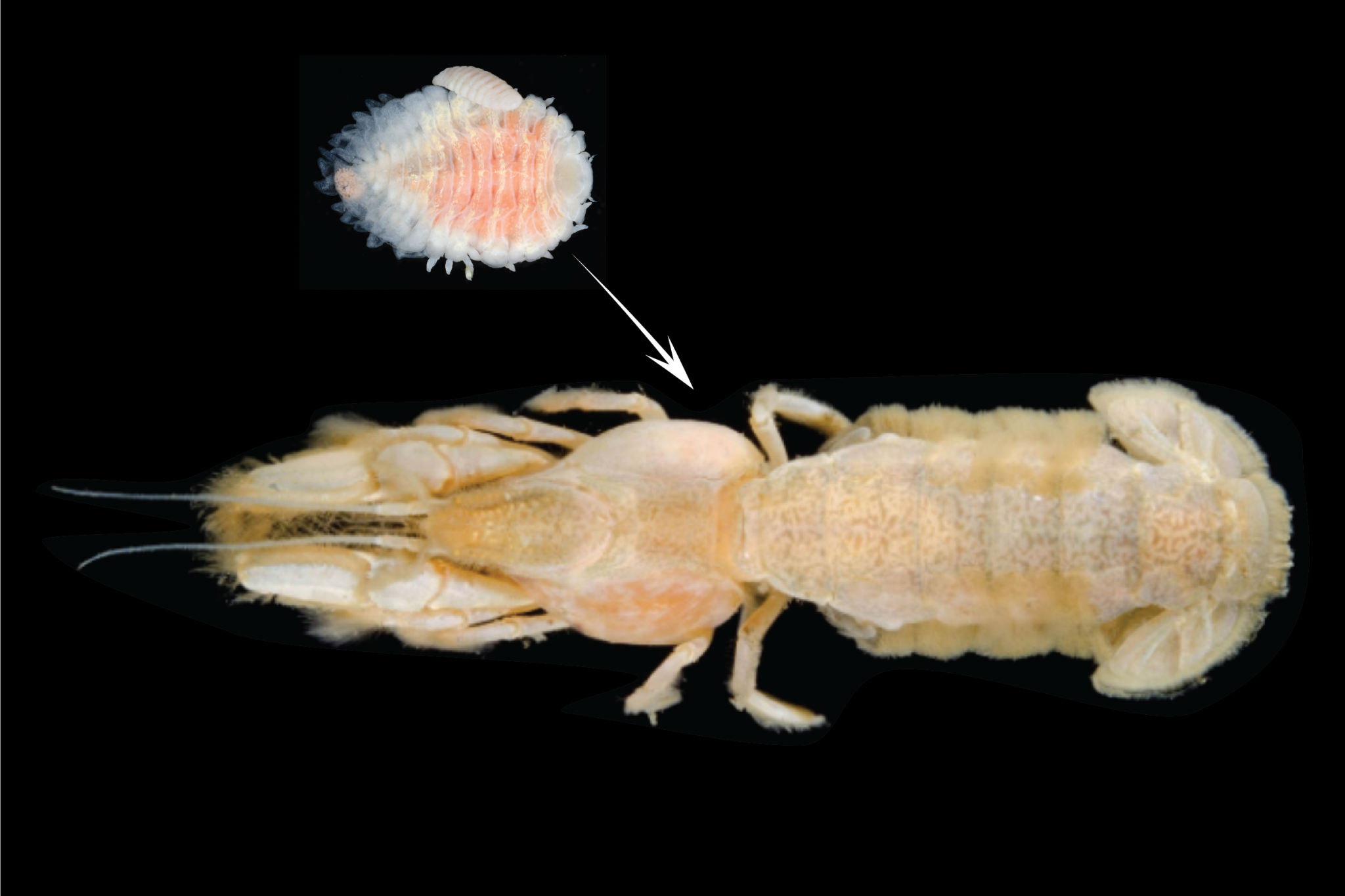

Home aquarists in North America and Europe are reporting Scutariella japonica more and more often. It seems to be the most common shrimp parasite. It is a Temnocephalidan, which is an order of tubellarian flatworms that usually lives in the shrimp’s gills or mantle. You can tell because it has a bunch of finger-like projections from its rostrum. It is known to naturally happen on Neocaridina populations in East Asia, which includes China, Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. Since the 1970s, live Neocaridina have been regularly brought into Japan for fishing in marine and brackish waters for fun, and they are also sold there in the aquarium trade. China became the main source for imported shrimps in the 1990s. A study by Niwa and Ohtaka showed that using live shrimp as bait helped Scutariella spread. Out of the 629 shrimp that were checked at Kansai Airport, 365 were infected. These shrimp were then sent to nearby areas. I myself have regularly seen infestations on Neocaridina shrimp, specifically those imported from Taiwan.

Neocaridina shrimp were collected from 18 sites in five provinces in Southeastern China from 2007 to 2009. The study was published in the Journal of Natural History. Of the 1,681 shrimp collected from 18 sites, most had at least one ectosymbiotic worm living on them, and S japonica occurred in 25. 2 to 100 percent of them. The affected shrimp had worms in the branchial chambers, cocoons that could be seen in the gills, and worms that could be seen on the surface of the rostrum.

Salt Cure Scutariella japonica is a parasite that only lives on shrimp. It eats trash in the water and the plasma of the shrimp. It sticks on with a suction cup base and lays its eggs in the gill chamber, usually in rows. The eggs can be seen and identified. When the shrimp molts, the eggs within the cocoons hatch and re-infect the colony. It is especially important to remove molts during and following treatment. On close examination, the infestation can be seen as a group of stalky parts sticking out from the rostrum above and between the eyes. Under magnification (a hand lens is very helpful), slow undulation of the parasites can be seen.

Because Scutalleria is spreading so quickly in aquariums and hobbyists’ tanks, it is very important to treat and visually inspect all colonies to stop the disease from spreading to healthy ones that are already there.

Luckily, Scutalleria is very easy to treat in several different ways. It works best for me to dip newcomers that are clearly infected in a solution that is 1 tablespoon of salt for every cup of tank water. The shrimp are placed in a well-oxygenated container for approximately 30 seconds, then removed. All visible parasites should be gone after this, and I have seen no shrimp mortality using this treatment. During treatment, it’s important to keep a close eye on the shrimp and take them away as soon as they show any signs of stress, like not moving or rolling over. ), then put them into fresh water immediately after treatment. The Asian Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances says that shrimp should be grown in slightly salty (5–10 ppt) conditions to keep them from getting sick or dying.

An alternative treatment is to use Praziquantel at a concentration of 2. 5mg/L in the tank. A single treatment usually works, but after a few weeks, a second one might be needed, especially if the molts aren’t taken out of the aquarium regularly. Some breeders have reported good results using Seachem’s ParaGuard.

Many other parasites are also becoming more common in freshwater shrimps. One of these is Vorticella, a ciliate protozoan that can be recognized by its noticeable ring of hair-like stalks that are arranged in clusters but attach to the rostrum and appendages separately. It can be treated in the same manner as Scutalleria japonica.

The parasitic protist tentatively identified as Ellobiopsis sp. appears as green, elliptical to elongate cylindrical stalks penetrating into the body of the shrimp. This pest can stop shrimp from moving and breeding, which usually leads to secondary bacterial infections that show up as cloudiness and whiteness on the shrimp’s body and eventually kill them. It’s not clear what the best way is to treat this pest; saline treatments don’t work, but it looks like this protist might be photosensitive, so an aquarium that is darkened and treated with anthelmintics might work.

Because shrimp pests are becoming a bigger problem, sellers and distributors should always treat and quarantine shrimps properly before sending them to stores and home aquariums.

Please let us know what you think. Have you dealt with these or any other parasites that affect freshwater shrimp? If so, please add your thoughts to our list.

References: Niwa, N. and A. Ohtaka. 2006. Accidental introduction of Symbionts with imported Freshwater shrimp. In: Koike, F. , et al. (eds), Assessment and Control of Biological Invasion Risks, World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland, pp. 182–86. Nur, F. A. H. and A. Christianus. 2013. Breeding and Life Cycle of Neocaridina denticulate sinensis (Kemp, 1918). Asian J Animal Vet Adv 8: 108–15. Ohtaka, S. R. , et al. 2012. Finding out where two types of ectosymbionts live on atyid shrimp (Arthropoda: Crustacea) in southeast China: branchiobdellidans (Annelida: Clitellata) and scutariellids (Platyhelminthes: “Turbellaria”: Temnocephalida). J Nat Hist 46 (25–26): 1547–56.

Shrimp are one of the most popular seafood options, prized for their sweet and briny flavor. From grilled shrimp skewers to classic shrimp scampi, they can be used in a variety of dishes. However, some people may wonder – do shrimp have parasites? What are the risks and how can you make sure any shrimp you eat is safe?

In this in-depth guide we’ll take a closer look at parasites in shrimp the types of parasites, assessing risks, proper handling and cooking, and what to do if you suspect an issue after eating shrimp. Armed with this knowledge, you can enjoy delicious shrimp dishes without worry.

Can Shrimp Have Parasites?

Yes, shrimp can sometimes have parasites However, the occurrence is relatively low, especially when proper precautions are taken

As aquatic animals, shrimp live in environments where they can naturally encounter parasites through things like contaminated water, predators, or other infected shrimp. Warm coastal waters tend to present a higher risk of parasite transmission.

Parasites that can infect shrimp include various worms protozoa, and viruses. They may invade the muscle tissue digestive tracts, or outer shells. Signs of parasitic infection are not usually visible to the naked eye.

So while they do occur occasionally, parasites in shrimp are quite uncommon, especially when raised in well-controlled aquaculture operations or caught from clean, cold-water environments.

Most Common Shrimp Parasites

There are a few main types of parasites that can be found in shrimp:

Nematodes – Tiny roundworms that can invade shrimp tissue. Includes species like Anisakis, Phocanema, and Pseudoterranova.

Cestodes – Segmented tapeworms. The broad fish tapeworm is one example found in shrimp.

Trematodes – Flukes which infect the shells and muscle tissue. Mainly consists of species like bucephalids.

Protozoa – Single-celled organisms like amoebas or ciliates that can occur on the surface.

Viruses – Such as Taura syndrome virus, white spot syndrome virus, and infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus.

While these parasites can certainly be present in shrimp, most do not pose significant risks to human health when the shrimp is properly handled and prepared. Some can cause mild illnesses like nausea or diarrhea if ingested alive.

Evaluating Parasite Risks in Shrimp

When assessing the risk of parasites in shrimp, key factors to consider include:

-

Water temperature – Shrimp from cold waters have lower risks than those from warm tropical areas where parasites thrive. Cold-water shrimp like those from Canada and the Northern U.S. are very low risk.

-

Wild-caught vs. farmed – Farmed shrimp raised in aquaculture systems have tighter controls to prevent parasite transmission. Wild-caught shrimp have higher exposure risks.

-

Cooking methods – Raw or undercooked shrimp poses higher risks for live parasites. Proper cooking kills most parasites.

-

Supply chain – Shrimp sourced from reputable suppliers, processors, and restaurants are more trustworthy.

-

Storage/handling – Prevent cross-contamination and temperature abuse when storing, thawing, and preparing shrimp.

By taking these factors into account and implementing proper food safety protocols, risks associated with parasites in shrimp are very low.

Proper Handling and Cooking

To help minimize any parasite risks with shrimp, adhere to safe storage, handling, and cooking:

-

Purchase fresh, raw shrimp from reputable sellers and supermarkets. Avoid already cooked or prepared shrimp.

-

Store raw shrimp below 40°F, wrapped in moisture-proof packaging or in ice. Use within 2 days.

-

When thawing frozen shrimp, do so in the refrigerator, cold water, or the microwave. Never at room temperature.

-

Wash hands, surfaces, utensils thoroughly before and after handling raw shrimp. Avoid cross-contamination.

-

Cook shrimp thoroughly to an internal temperature of 145°F. This kills any potential parasites.

-

When in doubt, freeze raw shrimp for 48 hours at -4°F or below to kill parasites before cooking.

By following proper protocols, you can feel confident that any shrimp you eat, whether at home, in a restaurant, or on vacation is safe to enjoy.

What If You Eat Shrimp With Parasites?

If you suspect you may have eaten undercooked or contaminated shrimp containing live parasites, symptoms to watch for may include:

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

- Fever, chills, muscle pain

- Itching, skin rash, hives

- Abdominal pain or discomfort

Seek medical care if symptoms are severe or persist more than a few days. Bring a sample of the suspect shrimp for testing, if possible.

Treatment may involve medication to eradicate parasitic infections, along with fluids and rest. Most cases resolve on their own or with minimal treatment.

The key is to prevent problematic parasites by sourcing safe shrimp and cooking it thoroughly when preparing your favorite shrimp dishes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are answers to some common questions about shrimp and parasites:

Are shrimp parasites visible?

Most parasites in shrimp cannot be seen with the naked eye. Proper handling and cooking should be followed regardless of visible signs.

Can you eat raw shrimp?

It’s not recommended. Raw or undercooked shrimp has higher risks for live parasites. Cook shrimp fully to eliminate risks.

Do shrimp parasites kill the shrimp?

Some parasites can eventually kill shrimp, while others allow the shrimp to survive while infected. Do not rely on the shrimp’s appearance to determine if parasites are present.

Are cooked shrimp safe from parasites?

Properly cooked shrimp does not pose a parasite risk. Cooking to an internal temperature of 145°F kills any potential parasites present.

Can lime or lemon juice kill parasites in shrimp?

No, marinating in citrus alone doesn’t guarantee killing parasites. Always cook shrimp thoroughly as an added safety measure.

The Bottom Line

While shrimp can sometimes harbor parasites, following basic food safety practices, choosing shrimp wisely, and proper cooking mitigates risks significantly. Implement preventive handling, source high-quality shrimp, and cook thoroughly to enjoy delicious, parasite-free shrimp every time. With these simple precautions, you can eat shrimp without worry and take advantage of its versatile, delectable flavor.