Fish come in astounding diversity, from giant whale sharks to tiny gobies. But regardless of size or species, all fish share a similar digestive system that allows them to obtain nutrients from the food they eat. This article explores how the fish digestive system functions, from ingestion to excretion.

Overview of the Fish Digestive Tract

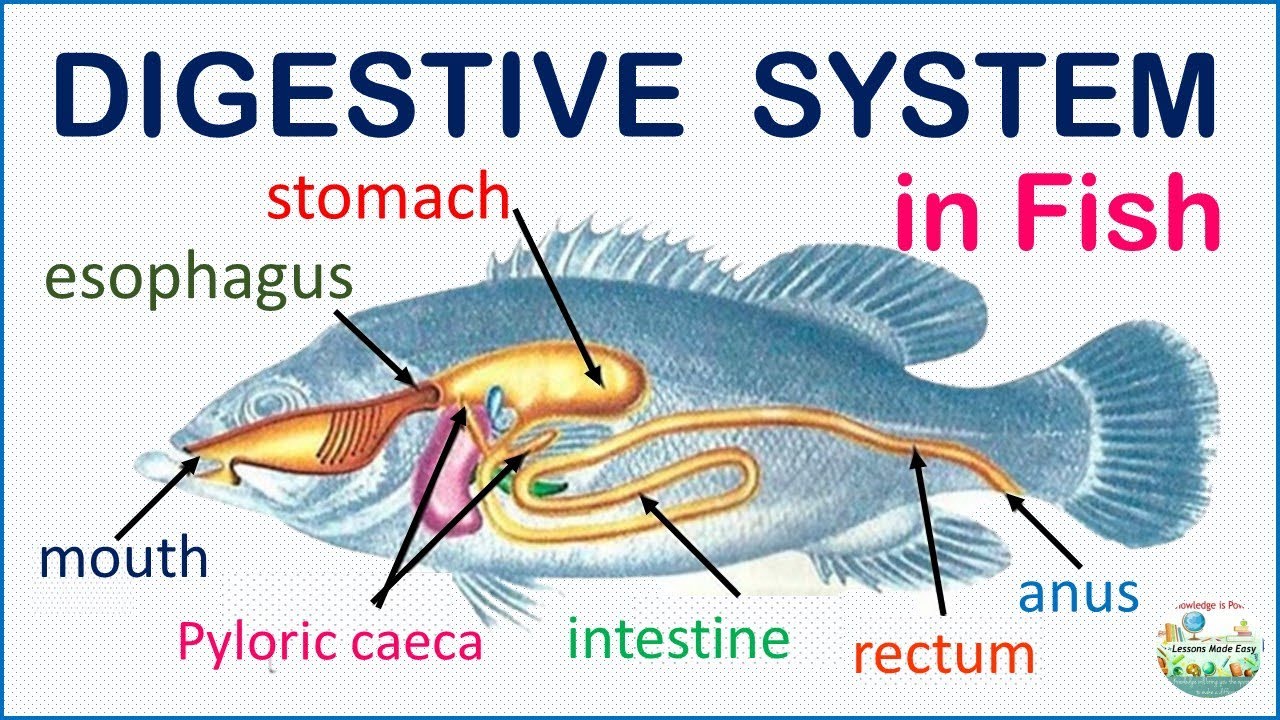

Like all vertebrates fish have a complete digestive tract consisting of a mouth, pharynx, esophagus stomach, intestine, and anus. Here are the key parts of the fish digestive system

-

Mouth – Fish mouths vary widely based on diet Most have jaws lined with teeth for grabbing prey Some have beak-like mouths or filter-feeding structures,

-

Pharynx – Also known as the throat, this transfers food from the mouth to the esophagus. Some fish have pharyngeal teeth for grinding food

-

Esophagus – A short, muscular tube that moves food from the pharynx to stomach via peristaltic contractions.

-

Stomach – Varies in structure and size based on diet. Key functions are storage, initial breakdown of food, and secretion of gastric juices.

-

Intestine – Absorbs nutrients from digested food into the bloodstream. Length depends on diet. Carnivores have short intestines while herbivores’ are longer.

-

Liver & Pancreas – Secrete digestive enzymes and bile for fat digestion into the intestine via ducts.

-

Cloaca – Found in cartilaginous fish and ray-finned fish, combines the intestinal tract with urogenital openings.

-

Anus – The muscular opening where undigested material exits the body.

Ingestion and Mechanical Digestion

Digestion begins at the mouth. Fish use their jaws and teeth to grasp, tear, and break food into smaller pieces. This mechanical digestion makes the food easier to chemically digest.

Fish mouths reflect their diet. Piscivores like barracuda have strong, fang-like teeth for piercing prey while herbivorous parrotfish have beak-like mouths and large pavement-like teeth for crunching coral. Omnivorous catfish may lack teeth altogether and swallow food whole.

Some fish have modified gill structures called gill rakers for filter feeding. Plankton-eating fish like menhaden use gill rakers to strain tiny organisms from the water.

After this initial mechanical breakdown, the food passes through the esophagus via peristalsis into the stomach.

Digestion in the Fish Stomach

Fish stomachs vary in structure and function based on species’ diets. However, key roles are:

-

Storage – Stomach acts as holding area, allowing fish to gulp prey quickly and digest later.

-

Mechanical digestion – Stomach churns and partially digests food via muscular contractions.

-

Chemical digestion – Gastric glands secrete acids, proteolytic enzymes like pepsin, and mucus to break down proteins.

In most fish, the stomach is a simple, J-shaped sac. But in filter-feeding fish like rays, it is more finely divided to increase surface area. Some fish like trout even have two stomachs – one for storage and one for digestion.

Nutrient Absorption in the Intestine

After initial digestion in the stomach, food moves into the intestine for further breakdown and absorption of nutrients.

Key functions of the fish intestine include:

-

Secretion of digestive enzymes from the liver and pancreas for chemical digestion.

-

Absorption of digested proteins, fats, and carbohydrates through the intestinal wall into blood and lymph.

-

Moistening and compaction of waste into feces.

To increase surface area for maximum nutrient uptake, the intestines have folds, villi, and microvilli. Since herbivores require longer digestion, plant-eating fish tend to have exceptionally long coiled intestines, sometimes several times their body length.

Excretion of Indigestible Material

Once the intestines have absorbed useful nutrients, all that remains is indigestible waste. This material passes from the anus as feces.

In cartilaginous fish like sharks, the digestive tract first empties into a cloaca before excretion. The cloaca collects waste from the intestinal, urinary, and reproductive tracts.

For most bony fish, the anus empties directly into the surrounding water. Some species produce liquidy waste while others generate solid feces bound in mucus.

Interestingly, fish feces actually contributes to the ecosystem. Microbes break down the nutrients and make them accessible to plants. So while waste to a fish, it fertilizes aquatic environments.

Special Digestive Adaptations in Fish

Over hundreds of millions of years, fish have evolved special adaptations that aid their digestion:

-

Pharyngeal jaws – Located in the throat, these enable fish like cichlids to process food after swallowing.

-

Pyloric caeca – Blind pouches near the stomach that increase surface area for digestion and absorption.

-

Spiral valve – Creates a corkscrew shaped intestine to slow food passage and maximize nutrient uptake.

-

Intestinal villi – Tiny finger-like projections in the intestine that absorb nutrients through the bloodstream.

These evolutionary innovations allow fish to extract the maximum benefit from the food they work so hard to capture and eat.

While fish display amazing diversity in size, shape, and habitat, the way they process food remains remarkably similar. From ingestion through mechanical and chemical digestion to nutrient absorption and waste excretion, the fish digestive system provides everything these aquatic vertebrates need to thrive on their specific diets. Subtle adaptations like pharyngeal jaws and pyloric caeca give different species an extra edge in getting the most out of the food they work hard to obtain.

Magazine of veterinary information, medicine and zootechnics, specialized in the poultry, pig, ruminant and aquaculture sectors

Advanced search Advanced search Search Content Category Tag Start date End date Author

Knowing and understanding the feeding and digestion in fish and its peculiarities is essential to produce feed and additives that fit their needs and feeding behavior.

Biovet S.A. – 5/03/2020