The species name “tshawytscha” comes from the common name used among natives in Alaska and Siberia.

Chinook salmon are the biggest salmon in the Pacific. They are usually 36 inches long and weigh more than 30 pounds. Adults can be told apart from juveniles by the black spots on their back and dorsal fins, as well as on both lobes of their caudal (tail) fin. Chinook salmon also have a black pigment along the gum line, thus the name “blackmouth” in some areas.

The Chinook salmon is a strong, deep-bodied fish that lives in the ocean. Its back is bluish-green and turns silvery on the sides, while the belly is white. Chinook salmon that are spawning in fresh water can be red, copper, or deep gray, depending on where they are and how mature they are. Males typically have more red coloration than females, which are typically gray. Males older than 4 to 7 years can be told apart from younger males by their “ridgeback” shape and hooked nose or upper jaw. Females are distinguished by a torpedo-shaped body, robust mid-section, and blunt noses. Juveniles in fresh water (fry) are recognized by well-developed parr marks which are bisected by the lateral line. Smolt Chinook salmon that are going to the ocean have bright silver sides, and the parr marks fade to mostly above the lateral line.

Like all species of Pacific salmon, Chinook salmon are anadromous. They hatch in fresh water and rear in main-channel river areas for one year. The following spring, Chinook salmon turn into smolt and migrate to the salt water estuary. They then spend anywhere from 1-5 years feeding in the ocean, and return to spawn in fresh water. All Chinook salmon die after spawning. Chinook salmon can be sexually mature between their second and seventh year. Because of this, the size of the fish in any spawning run can vary a lot. A mature 3-year-old, for example, may weigh less than 4 pounds, while a mature 7-year-old may weigh more than 50 pounds. Females tend to be older than males at maturity. In many spawning runs, males outnumber females in all but the 6- and 7-year age groups. Small Chinook salmon that become adults after only one winter in the ocean are called “jacks,” and they are usually male. Alaska streams normally receive a single run of Chinook salmon in the period from May through July.

Chinook salmon often have long journeys through fresh water to get to their home streams in some of the bigger river systems. In 60 days, spawners on the Yukon River will travel more than 2,000 river miles to get to the very beginnings of the river in Yukon Territory, Canada. While they are migrating to spawn in fresh water, Chinook salmon don’t eat, so their health slowly gets worse as they use stored body fat for energy and gonad development.

Each female lays between 3,000 and 14,000 eggs in a number of gravel nests, or redds, that she digs out in water that is fairly deep and moving quickly. Depending on when they spawn and how warm the water is, Alaskan salmon eggs usually hatch in late winter or early spring. Alevins, the fish that have just hatched, live in the gravel for a few weeks until they start to eat the food in the attached yolk sac. These juveniles, called fry, wiggle up through the gravel by early spring. Chinook juveniles divide into two types: ocean type and stream type. Ocean type Chinook migrate to saltwater in their first year. Stream type spend one full year in fresh water before migrating to the ocean. In Alaska, most young Chinook salmon stay in fresh water until spring, when they move to the ocean as smolt, when they are two years old.

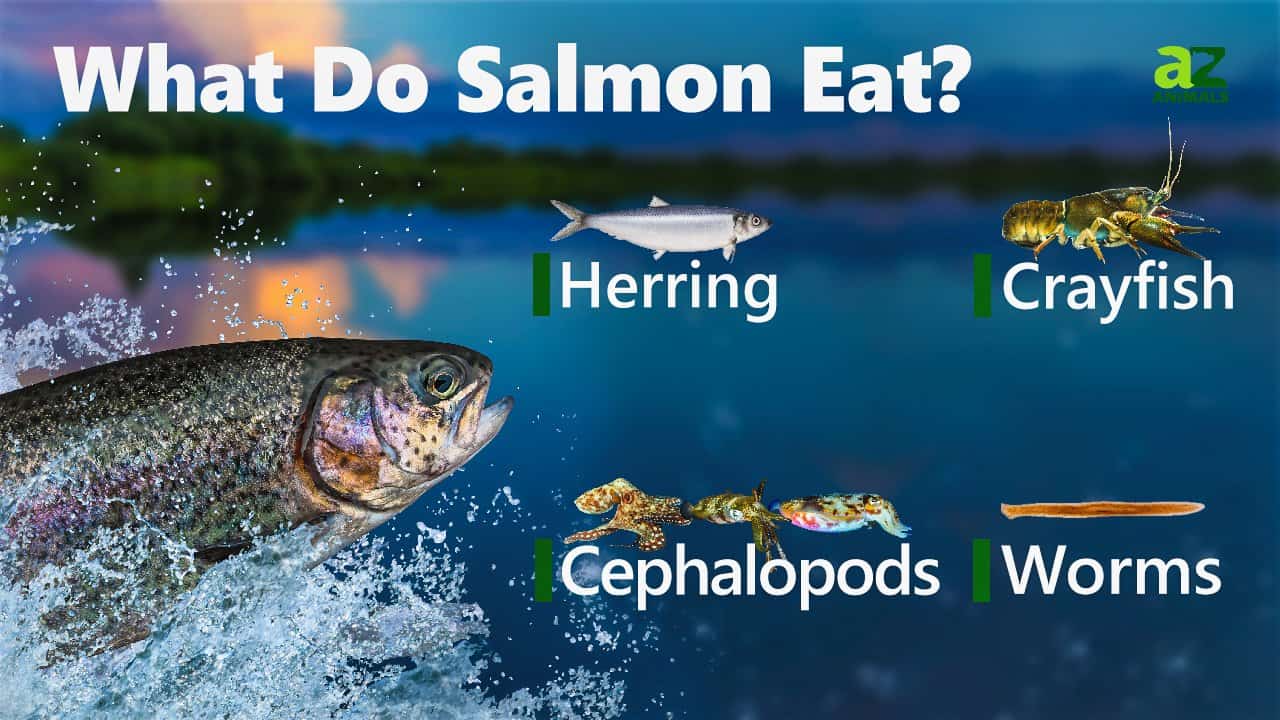

Juvenile Chinook salmon in fresh water initially feed on plankton and later feed on insects. In the ocean, they eat a variety of organisms including herring, pilchard, sandlance, squid, and crustaceans. Salmon grow rapidly in the ocean and often double their weight during a single summer season.

Streams and estuaries with fresh water are important places for chinook salmon to spawn, and they are also good places for eggs, fry, and juveniles to grow up. When it comes to North America, Chinook salmon live from California’s Monterey Bay to Alaska’s Chukchi Sea. On the Asian coast, Chinook salmon occur from the Anadyr River area of Siberia southward to Hokkaido, Japan. In Alaska, they are abundant from the southeastern panhandle to the Yukon River. Major populations return to the Yukon, Kuskokwim, Nushagak, Susitna, Kenai, Copper, Alsek, Taku, and Stikine rivers. Important runs also occur in many smaller streams.

Chinook salmon, also known as king salmon, are an iconic fish species found along the Pacific coast of North America. Characterized by their large size and buttery orange flesh, chinook salmon are highly prized by anglers and seafood lovers. But what do these mighty fish eat to grow so big? The answer is that chinook salmon have a diverse diet that changes as they mature.

Young Chinook Salmon

In their early life stages, juvenile chinook salmon feed on a range of small prey items. According to NOAA Fisheries, young chinook salmon consume terrestrial and aquatic insects, amphipods, and other small crustaceans.

Some key facts about the diet of juvenile chinook

-

Terrestrial insects such as grasshoppers, ants, beetles, and flies make up an important part of their diet These insects fall into the water and provide a rich source of nutrients for young salmon

-

Aquatic insects like mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies are also eaten by juvenile chinook. These bugs live on the bottoms of streams and rivers.

-

Amphipods, also known as scuds, are shrimp-like crustaceans that become more important in the diet as chinook grow bigger.

-

Other crustaceans consumed include isopods, copepods, and ostracods. These small aquatic creatures are packed with protein.

In addition to insects and crustaceans young chinook will also feed on plankton and fish eggs during their time rearing in freshwater. Their diverse diet provides the nutrients and energy needed to fuel rapid growth.

Adult Chinook Salmon

Once chinook salmon migrate out to the ocean and begin maturing, their diet shifts to focus more on fish. According to the National Wildlife Federation, adult chinook salmon are aggressive predators that hunt a variety of fish species.

NOAA Fisheries says that older chinook fish eat mostly other fish, like smelts, anchovies, and herring. Some specifics on their adult diet:

-

Pacific whiting and mackerel become important prey items as chinook grow larger offshore. These schooling fish provide a concentrated source of nutrition.

-

Chinook are opportunistic feeders and will also eat squid, crabs, and shrimp. This supplements their primary fish diet.

-

Cannibalism is not uncommon among adult chinook, with large individuals eating smaller members of their own species.

The protein and oils provided by fish allow adult chinook to rapidly gain weight before making their spawning migrations back to freshwater. A mature 30-pound chinook may consume over a pound of prey fish per day while at sea.

Natural Predators

Young and adult chinook salmon also play an important role in the food chain as prey for other species. According to NOAA, birds and larger fish prey on juvenile chinook in estuaries and coastal areas.

-

Sea birds such as terns, cormorants, and gulls snatch small chinook from shallow waters.

-

Larger fish like lingcod and rockfish ambush and consume young salmon.

-

Harbor seals are also effective predators of juvenile chinook, patrolling mouths of rivers.

In the open ocean, sharks and marine mammals are the primary natural predators of adult chinook.

-

Sharks including great whites and makos hunt mature chinook during their ocean phase.

-

Orcas and sea lions pursue adult salmon and are specialized salmon hunters.

-

Occasionally bears, eagles, and other wildlife catch adult chinook returning to spawn.

This natural cycle highlights the important connections between chinook and other species throughout their range along the Pacific Coast.

Status, Trends, and Threats

National Status: N4 (Apparently Secure)

Implied Status under the U. S. Endangered Species Act: PS (Partial Status – status in only a portion of the species range.

Trends and Threats: There are many stocks of Chinook in the state, and their population trends are also very different. Some stocks are going down, while others are staying the same or going up. Threats include overfishing, dams, habitat loss, habitat degradation, and climate change.

- Size: Length: 36 inches (old record: 58 inches); Weight: 30 pounds (old record: 126 pounds)

- Lifespan 3 to 7 years

- Range: North America, from Monterey Bay, California, to the Chukchi Sea Asia – Hokkaido, Japan to Anadyr River, Siberia .

- Diet / Feeding Type Plankton, insects, amphipods, and fish

- Predators Birds and fish eat juveniles; marine mammals eat adults

- Reproduction Anadromous and semelparous

- Notes: The Chinook salmon was named the official state fish of Alaska on March 25, 1963.

- Other Names Chinook, chins, king. quinnat, tyee, tule, blackmouth, and spring salmon.

- 3% of Chinook have white meat.

- Chinook spend 1 to 7 years at sea.

- The common name used by people who live in Alaska and Siberia is where the species name “tshawytscha” comes from.

- Chinook are Alaska’s state fish.

- Because they are so big, Chinook salmon are called “Kings.”

- A Chinook salmon went 3,845 km upstream to spawn, which is the farthest trip any salmon is known to have ever taken.

One of Alaska’s most important industries depends on Pacific salmon coming back to rivers and streams to have babies. Five years, from 2014 to 2018, the average number of Chinook salmon caught each year was 382,373 fish, weighing 4,549,446 pounds, and having an estimated value of $20,873,025 when taken off the boats. Commercially-harvested Chinook salmon averaged approximately 12 pounds during that period. The majority of the Alaska catch is made in Southeast Alaska, Bristol Bay, and the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim areas. The majority of the catch is made with troll gear and gillnets. There is an excellent market for Chinook salmon because of their large size and excellent table qualities.

The law says that this type of fishing is “the taking, attempting to take, or possession of finfish, shellfish, or aquatic plants by a person in Alaska for food or bait by that person or his immediate family.” Only Alaska residents may participate in personal use fisheries. The Board of Fisheries set up this fishery so that Alaskans could catch fish for food in places that weren’t allowed for subsistence fisheries. Personal use fisheries are only allowed if they won’t hurt the resource’s long-term yield, won’t interfere with how the resource is already being used, and are in the public’s best interest. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Sport Fish Division is in charge of most personal use fishing. The Division of Commercial Fisheries, on the other hand, is in charge of some regional or area fisheries for different species of fish.

Chinook salmon are one of the most sought-after sport fish in Alaska. A lot of people fish for them in Southeast Alaska and Cook Inlet (south-central Alaska). In salt water, trolling with rigged herring is the best way to fish. In fresh water, lures and salmon eggs are used. The annual Alaska sport fishing harvest of Chinook salmon from 1989 to 2006 averaged 170,000 fish. During that time, 60% of the sport salmon harvest in Alaska took place in south-central Alaska, 26% in southeast Alaska, and 4% in the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim area. Alaskas sport and personal use fisheries worth more than 500 million dollars annually.

Many Alaskans depend heavily on subsistence-caught salmon for food and cultural purposes. Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game says that subsistence fishing is when a resident of the state uses a gill net, seine, fish wheel, long line, or another method approved by the Board of Fisheries to catch fish, shellfish, or other fisheries resources for their own personal needs. From 1994 to 2005, Alaskans who fished for food or fun caught an average of 167,000 Chinook salmon each year. The majority of the subsistence harvest is taken in the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers.

The Alaska State Constitution says that the state will develop and use resources that can be used again and again, following the principle of sustained yield, so that the people of the state can get the most out of them. The Alaska Board of Fisheries (BOF) and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF) were set up by the Alaska Legislature to carry out this policy for the state’s fisheries resources.

The BOF was given the job of making rules for the protection and growth of the state’s fisheries resources, including how the benefits should be shared between subsistence, commercial, recreational, and personal uses. The ADF Scientific and technical advice is also provided by the ADF&G to the BOF during its rule-making process. Most people think that the fact that these two groups are not responsible for making rules and managing fish during the season is a good thing for Alaska’s fisheries management system.

The division’s fishery management activities fall into two categories: inseason management and applied science. For inseason management, the division deploys a cadre of fishery managers near the fisheries. These people have a lot of power to open and close fisheries based on their professional opinion, the most recent biological data from field projects, and how well the fisheries are doing. Research biologists and other specialists conduct applied research in close cooperation with the fishery managers. It is the job of the division’s research shop to make sure that Alaska’s fisheries resources are managed in line with the sustained yield principle and that managers have the technical help they need to make sure that fisheries are managed using the best biological data and sound scientific principles. In both management and research tasks, the division works closely with the Division of Sport Fisheries.

The Pacific Salmon Treaty provides harvest sharing arrangements that guide fisheries. By ratifying the Pacific Salmon Treaty in 1985, the US and Canada agreed to work together to protect, study, and improve Pacific salmon stocks that were important to both countries. The Pacific Salmon Commission is an international group that makes decisions. It is made up of four Commissioners (and four alternates) from the US and Canada. This group is in charge of running the Pacific Salmon Treaty with help from four regional panels of fisheries experts. Several technical committees made up of salmon scientists from each country give scientific advice on salmon populations and the right way to control the fishery.

According to experts, research is a key part of getting to know wildlife populations better, which is necessary for making good management plans. Every year, many different types of research are done all over the state. These studies look into many different areas, such as population dynamics, genetics, life histories, species interactions, wildlife monitoring technologies, and stock structure. Such projects are often conducted in collaboration with university, federal and international institutions. Researchers from around the world read and comment on these works, which are then published as articles and shown at scientific meetings and conferences around the world.

Unalakleet smolt research. A general overview about the smolt study on the Unalakleet River in 2011. We talk briefly about the screw trap, how the smolt are studied, and why the study is important. About 6 minutes. Produced by Dan Foster – ZONK! Productions Inc. and segment used with permission.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Jump to species:

The species name “tshawytscha” comes from the common name used among natives in Alaska and Siberia.

Chinook salmon are the biggest salmon in the Pacific. They are usually 36 inches long and weigh more than 30 pounds. Adults can be told apart from juveniles by the black spots on their back and dorsal fins, as well as on both lobes of their caudal (tail) fin. Chinook salmon also have a black pigment along the gum line, thus the name “blackmouth” in some areas.

The Chinook salmon is a strong, deep-bodied fish that lives in the ocean. Its back is bluish-green and turns silvery on the sides, while the belly is white. Chinook salmon that are spawning in fresh water can be red, copper, or deep gray, depending on where they are and how mature they are. Males typically have more red coloration than females, which are typically gray. Males older than 4 to 7 years can be told apart from younger males by their “ridgeback” shape and hooked nose or upper jaw. Females are distinguished by a torpedo-shaped body, robust mid-section, and blunt noses. Juveniles in fresh water (fry) are recognized by well-developed parr marks which are bisected by the lateral line. Smolt Chinook salmon that are going to the ocean have bright silver sides, and the parr marks fade to mostly above the lateral line.

Like all species of Pacific salmon, Chinook salmon are anadromous. They hatch in fresh water and rear in main-channel river areas for one year. The following spring, Chinook salmon turn into smolt and migrate to the salt water estuary. They then spend anywhere from 1-5 years feeding in the ocean, and return to spawn in fresh water. All Chinook salmon die after spawning. Chinook salmon can be sexually mature between their second and seventh year. Because of this, the size of the fish in any spawning run can vary a lot. A mature 3-year-old, for example, may weigh less than 4 pounds, while a mature 7-year-old may weigh more than 50 pounds. Females tend to be older than males at maturity. In many spawning runs, males outnumber females in all but the 6- and 7-year age groups. Small Chinook salmon that become adults after only one winter in the ocean are called “jacks,” and they are usually male. Alaska streams normally receive a single run of Chinook salmon in the period from May through July.

Chinook salmon often have long journeys through fresh water to get to their home streams in some of the bigger river systems. In 60 days, spawners on the Yukon River will travel more than 2,000 river miles to get to the very beginnings of the river in Yukon Territory, Canada. While they are migrating to spawn in fresh water, Chinook salmon don’t eat, so their health slowly gets worse as they use stored body fat for energy and gonad development.

Each female lays between 3,000 and 14,000 eggs in a number of gravel nests, or redds, that she digs out in water that is fairly deep and moving quickly. Depending on when they spawn and how warm the water is, Alaskan salmon eggs usually hatch in late winter or early spring. Alevins, the fish that have just hatched, live in the gravel for a few weeks until they start to eat the food in the attached yolk sac. These juveniles, called fry, wiggle up through the gravel by early spring. Chinook juveniles divide into two types: ocean type and stream type. Ocean type Chinook migrate to saltwater in their first year. Stream type spend one full year in fresh water before migrating to the ocean. In Alaska, most young Chinook salmon stay in fresh water until spring, when they move to the ocean as smolt, when they are two years old.

Juvenile Chinook salmon in fresh water initially feed on plankton and later feed on insects. In the ocean, they eat a variety of organisms including herring, pilchard, sandlance, squid, and crustaceans. Salmon grow rapidly in the ocean and often double their weight during a single summer season.

Streams and estuaries with fresh water are important places for chinook salmon to spawn, and they are also good places for eggs, fry, and juveniles to grow up. When it comes to North America, Chinook salmon live from California’s Monterey Bay to Alaska’s Chukchi Sea. On the Asian coast, Chinook salmon occur from the Anadyr River area of Siberia southward to Hokkaido, Japan. In Alaska, they are abundant from the southeastern panhandle to the Yukon River. Major populations return to the Yukon, Kuskokwim, Nushagak, Susitna, Kenai, Copper, Alsek, Taku, and Stikine rivers. Important runs also occur in many smaller streams.

King Salmon / Chinook Salmon – Fun Facts & Fishing

FAQ

What type of fish do Chinook salmon eat?

What is the best bait for Chinook salmon?

How much do Chinook salmon eat?

Do Chinook salmon eat crabs?

What do Chinook salmon eat?

Young Chinook salmon like to eat insects and small crustaceans, particularly amphipods. Adult salmon dine mostly on other fish. Chinook salmon are anadromous, which means they are born in freshwater streams and travel to the open ocean to grow into adulthood. For the first year or so, the juvenile salmon stays in its freshwater habitat.

What Tribes EAT Chinook fish?

Other tribes, including the Nuxalk, Kwakiutl, and Kyuquot, relied primarily on Chinook to eat. Known as the “king salmon” in Alaska for its large size and flavorful flesh, the Chinook is the state fish of this state, and of Oregon.

Why is Chinook salmon important?

It is a vital food source for a diversity of wildlife, including orcas, bears, seals, and large birds of prey. Chinook salmon are also prized by people who harvest salmon both commercially and for sport. The health of Chinook salmon depends on location—Alaskan stocks are very healthy, while those in the Columbia River are in danger.

What is a Chinook salmon?

The Chinook salmon ( Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) is the largest and most valuable species of Pacific salmon. Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other vernacular names for the species include king salmon, Quinnat salmon, Tsumen, spring salmon, chrome hog, Blackmouth, and Tyee salmon.