I almost always tell my pet turkey, Woodford, this. When people hear me say it, they give me a suspicious look. That’s because the majority of people are unaware of what a “snood” is!

Actually, I was also unaware of this until a few years ago. However, I had to find out when my flock of male turkeys began to mature and developed what was obviously the facial equivalent of a penis on their faces.

Read on for an inside look at some amazing things every turkey owner, admirer, or eater should know if you have any questions about turkey anatomy that you’re hesitant to address in public.

The anatomy of a turkey particularly its reproductive organs, is a topic that has sparked curiosity and raised questions among many. While turkeys are known for their distinctive gobbles and impressive plumage their penises remain a less-discussed aspect of their biology. This comprehensive guide delves into the fascinating world of turkey penises, exploring their unique appearance, function, and evolutionary significance.

Anatomy of a Turkey Penis

Unlike mammals, turkeys possess a phallus, which is a non-erectile organ responsible for delivering sperm during mating. The turkey phallus is located beneath the cloaca, a multi-purpose opening that serves as the exit point for both the digestive and reproductive tracts.

The phallus itself is a relatively small, corkscrew-shaped structure, typically measuring around 2-3 inches in length. It is composed of two main parts: the shaft and the glans. The shaft is the main body of the phallus, while the glans is the bulbous tip that contains the opening for sperm release.

Appearance and Function

The turkey phallus is characterized by its corkscrew-like shape, which is believed to enhance sperm delivery during mating. The glans, with its sperm-releasing opening, is positioned at the end of the corkscrew, ensuring efficient transfer of genetic material.

During mating, the male turkey mounts the female and inserts his phallus into her cloaca. The corkscrew shape of the phallus allows it to penetrate deep into the female’s reproductive tract, increasing the chances of fertilization.

Evolutionary Significance

The unique anatomy of the turkey phallus is a product of millions of years of evolution. The corkscrew shape is thought to have evolved as a way to improve sperm competition. By ensuring that the sperm is deposited deep within the female’s reproductive tract, the male turkey increases the likelihood of his sperm fertilizing the eggs.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Do all male turkeys have a penis?

Yes, all male turkeys have a phallus. However, the size and shape of the phallus can vary slightly between individual birds.

2. Is the turkey phallus visible?

No, the turkey phallus is not typically visible. It is located beneath the cloaca and only emerges during mating.

3. Can turkeys mate without a penis?

No, turkeys require a phallus for successful mating. The phallus is essential for delivering sperm to the female’s reproductive tract.

4. Is the turkey phallus similar to a human penis?

No, the turkey phallus is significantly different from a human penis. It is non-erectile and has a corkscrew shape, unlike the cylindrical shape of a human penis.

5. What is the purpose of the corkscrew shape?

The corkscrew shape of the turkey phallus is believed to enhance sperm delivery during mating. It allows the phallus to penetrate deep into the female’s reproductive tract, increasing the chances of fertilization.

The turkey phallus, with its unique corkscrew shape and non-erectile nature, plays a crucial role in turkey reproduction. Its evolutionary significance highlights the importance of adaptation and competition in the animal kingdom. While the turkey phallus may not be as widely discussed as other aspects of turkey biology, its fascinating anatomy and function offer a glimpse into the complex world of avian reproduction.

Strutting, Spitting, and Drumming

Small muscles at the beginning of each feather enable those displays of wing and tail feathers. Toms can stand their feathers upright by flexing their muscles at will. They are also capable of holding a flexed posture for protracted periods of time.

When they do, this is what we call strutting. Toms show off their amazing good looks to everyone in the vicinity.

Males occasionally make a ticking or tsking sound with their beaks while strutting. This is sometimes called “spitting”. Sometimes liquid is ejected during this process.

Additionally, turkeys have a kind of drumming sound coming from their body. In my opinion, it sounds like a hydraulic or compression system in operation.

The details of how and why turkey toms perform these behaviors are scarce. However, based on my observation of my turkey Woodford, he appears to do so more frequently in front of sizable crowds of admirers or after strutting for a while.

To the best of my knowledge, spitting allows him to take a deep breath by temporarily moving his snood and clearing his nostrils. He also opens his mouth at the same time.

In order for him to keep his flexed feather position, the drumming appears to be like pulling in a power boost. His entire body trembles as a result, and he frequently shuffles his steps. Then, his body and his feathers also appear more erect. He frequently tilts his tail fan more frequently after drumming and spitting.

Some claim that even when they are not strutting, turkeys spit and drum. Personally, I’ve never witnessed my turkey do anything other than strut when he’s not I have also never heard a female turkey drum.

Just like chickens, turkeys have an annual molt. Thankfully, they do! By the end of the mating season, male turkeys can appear quite worn out from dragging their wing feathers for fighting and strutting.

Additionally, the mating process frequently wears out female turkeys, so they require new feathers before winter.

Meet My Bourbon Red – Woodford

Woodford is a Bourbon Red Turkey. He belongs to a select class of turkeys known as heritage breeds. Among them are a number of Woodford’s exquisite feathered companions, such as the Jersey Buff, Midget White, Beltsville Small Whites, Narragansetts, Slates, Blacks, and White Hollands.

I bring this up because, before they exhibit the majestic qualities I am about to describe, the majority of non-heritage breed turkeys end up on the dinner table. However, heritage breeds live longer because they are raised for flavor and mature considerably more slowly than the typical white turkeys you find in the freezer at your grocery store.

Heritage breed turkeys are also able to naturally reproduce. These turkeys are kept by so many people for mating, laying, and hatching eggs.

Now, it’s possible that the anatomy of a commercial breed turkey will exhibit these characteristics. But, heritage breed and wild turkeys generally have a higher chance of exhibiting them.

There’s no denying that one of the most amazing sights you can witness in the woods or on a homestead is a male turkey, known as a Tom, in full feather. If you pay attention to the details, a mature Tom is almost as stunning as a peacock, in my humble opinion.

To find out why, let’s examine the anatomy of turkeys in more detail.

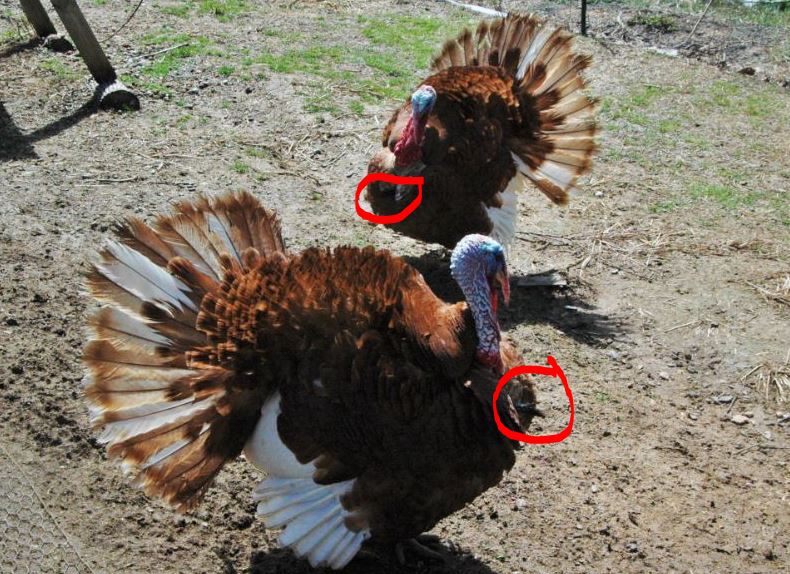

That snood I described earlier is a piece of flesh that rests on the forehead of a young turkey, resembling a unicornhorn. It initially seems to be the same in male and female turkeys. However, as the males begin to maturesexually their snoods elongate.

Snood size increases with age. Additionally, it grows longer during strutting and contracts during resting. The snood of older male turkeys is frequently so long that it is difficult to see when the bird is at rest.

The snood also changes colors. The resting color of the snood varies by breed. They usually range from pinkish to red. Turkey snoods become darker red when they strut, especially if they do so for extended periods of time.

When viewed from a human viewpoint, the snood appears to be an extremely inconvenient device. It frequently blocks a turkey’s nostrils, making it difficult for the bird to breathe deeply. Additionally, because of its position, males with long snoods find it more difficult to pick seeds from plants or peck at food that is on the ground.

Male turkeys frequently pull on each other’s snoods with their beaks during fights to determine who is in the pecking order. For several minutes, until the other turkey either gives up or gets free, one turkey will pull the other around by their neck.

Long snoods are supposedly preferred by turkey hens despite these inherent complications. The turkey equivalent of displaying virility is a long snood.

The lumpy caruncles that encircle the base of the male turkey’s neck like a red scarf are another remarkable characteristic. These are called the major caruncles.

Caruncles are also the mottled coagulation of shiny, leather-like skin that runs down the necks of turkeys and encircles their heads like hoods. When a turkey is excited, its caruncles typically turn a deep red color. However, near the eye area, the caruncles turn blue instead.

By constricting the blood vessels in their caruncles, turkeys can alter the color of their caruncles. This kind of work like muscles being flexed.

Male and female turkeys both have caruncles. Nonetheless, a turkey’s caruncles get thicker the more testosterone it contains. So males have more obvious caruncles than females. Additionally, when a turkey is excited, the color of its caruncles gets deeper the more testosterone it has.

A wattle grows along the neck line of turkeys, beneath their chins. It is indistinguishable from the caruncles unless a turkey is sticking out its neck. It is essentially a thin, floppy fold of skin when it is at rest.

Wattles are used to help regulate body temperature. You may see turkeys extending their necks to show off their wattles when they get hot. Turkeys tuck their wattles under their chins to make them almost invisible when they’re cold.

Females have shorter, narrower wattles than males. In addition, females are smaller, have fewer feathers, and are spared the labor-intensive strutting and fighting that males do. It follows that their ability to control their body temperature would not require Tom-sized wattles.

The beard has the appearance and texture of long, black plastic bristles from a broom. Some people liken it to a horsetail. Turkey hunters often collect beards as souvenirs of their kill.

When young turkeys with short beards strut, their beards stand erect. The beard of older turkeys with long beards hangs low, just below the feather line. Beards grow with age.

Wild turkeys tend to have longer beards than domesticated turkeys. Wild turkey beards can grow up to a foot long. Although they are much shorter and less noticeable than male beards, females can also grow beards.

Toms naturally have large spurs as part of their anatomy, just like roosters do. Spurs can grow on females, but they are typically rounder and less prominent. (Turkey feet also appear distinctly pterodactyl-like, in my opinion. ).

When at rest, male and female turkey feathering appears similar. Other than being distinctly smaller than males, females can be hard to tell apart from males just by looking at their feathers.

However, the feather differences become distinctly different when a male turkey struts.

The tail feathers of male turkeys resemble those of a peacock. They are used primarily for show.

They stand erect like a fan. When standing straight, the turkey can aim them at their intended audience by angling them from left to right like a ship’s rudder.

Females can also fan their tail feathers in similar displays. However, they never achieve the same upright positioning. They also don’t maintain it as long. When females use it, it’s usually not for pure show but rather to establish a pecking order with other females.

Male turkeys also use their wing feathers more for display or for fighting than for flying. When at rest, they blend in with the feathers in the belly and tuck up along the body.

In males, they descend to the ground when they strut. The feathers scrape the ground on rocky or uneven terrain, and sanding breaks or shaves off the tips. When standing, females almost never have their wings lowered to the ground.

When fighting, toms also spread their wings to give off a more menacing appearance. They will also use their wings as weapons and as arms to defeat their adversary.

Additionally, as they mount submissive females for mating, male turkeys use their wings to enfold them.