Hams: They can be fresh, cook-before-eating, cooked, picnic and country types. There are so many kinds, and their storage times and cooking times can be quite confusing. This background information serves to carve up the facts and make them easier to understand.

Hams may be fresh, cured or cured-and-smoked. Ham is the cured leg of pork. Fresh ham is an uncured leg of pork. There will be the word “fresh” in the name of fresh ham, which means that it has not been cured. “Turkey” ham is a ready-to-eat product made from cured thigh meat of turkey. The term “turkey ham” is always followed by the statement “cured turkey thigh meat. “.

Cursed ham is usually a deep rose or pink color. Fresh ham, which isn’t cured, is the color of a fresh pork roast, which is pale pink or beige. Country hams and prosciutto, which are dry-cured, are pink to mahogany.

Hams are either ready-to-eat or not. Ready-to-eat hams include prosciutto and cooked hams; they can be eaten right out of the package. People must cook fresh hams and hams that have only been treated to destroy trichinae (this could mean heating, freezing, or curing in the processing plant) before they can eat them. Hams that must be cooked will bear cooking instructions and safe handling instructions.

If a ham isn’t ready to eat but looks like it is, it will have a big message on the main display panel (label) saying that it needs to be cooked, examples g. , “cook thoroughly. ” In addition, the label must bear cooking directions.

Sodium or potassium nitrate (or saltpeter), nitrites, and sometimes sugar, seasonings, phosphates, and cure accelerators are added to make something cure. g. , sodium ascorbate, to pork for preservation, color development and flavor enhancement.

Nitrate and nitrite contribute to the characteristic cured flavor and reddish-pink color of cured pork. Clostridium botulinum is a deadly microorganism that can grow in foods in some situations. Nitrite and salt stop it from growing.

Pork can be injected with flavoring and curing solutions or massaged and tumbling the solutions into the muscle. Both methods make the pork more tender.

For dry curing, which is how country hams and prosciutto are made, fresh ham is rubbed with a dry-cure mix of salt and other things. Dry curing produces a salty product. In 1992, U. S. The USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) approved a trichinae treatment method that lets potassium chloride be used instead of up to half of the sodium chloride. This lowers the amount of sodium in the food. Since dry curing takes away the moisture, the weight of the ham is reduced by at least 20%, but usually by up to 25%. This makes the flavor more concentrated.

Dry-cured hams may be aged more than a year. Six months is the traditional process but may be shortened according to aging temperature.

These hams that haven’t been cooked can be kept at room temperature without getting spoiled by bacteria because they don’t have much water in them. Dry-cured ham is not injected with a curing solution or soaked in a curing solution to make it, but it can be smoked. Today, dry-cured hams may be sold as items that need to be prepared by the customer before they are safe to eat. Just like with any other meat, it’s important to read the label on a ham to see how it should be cooked.

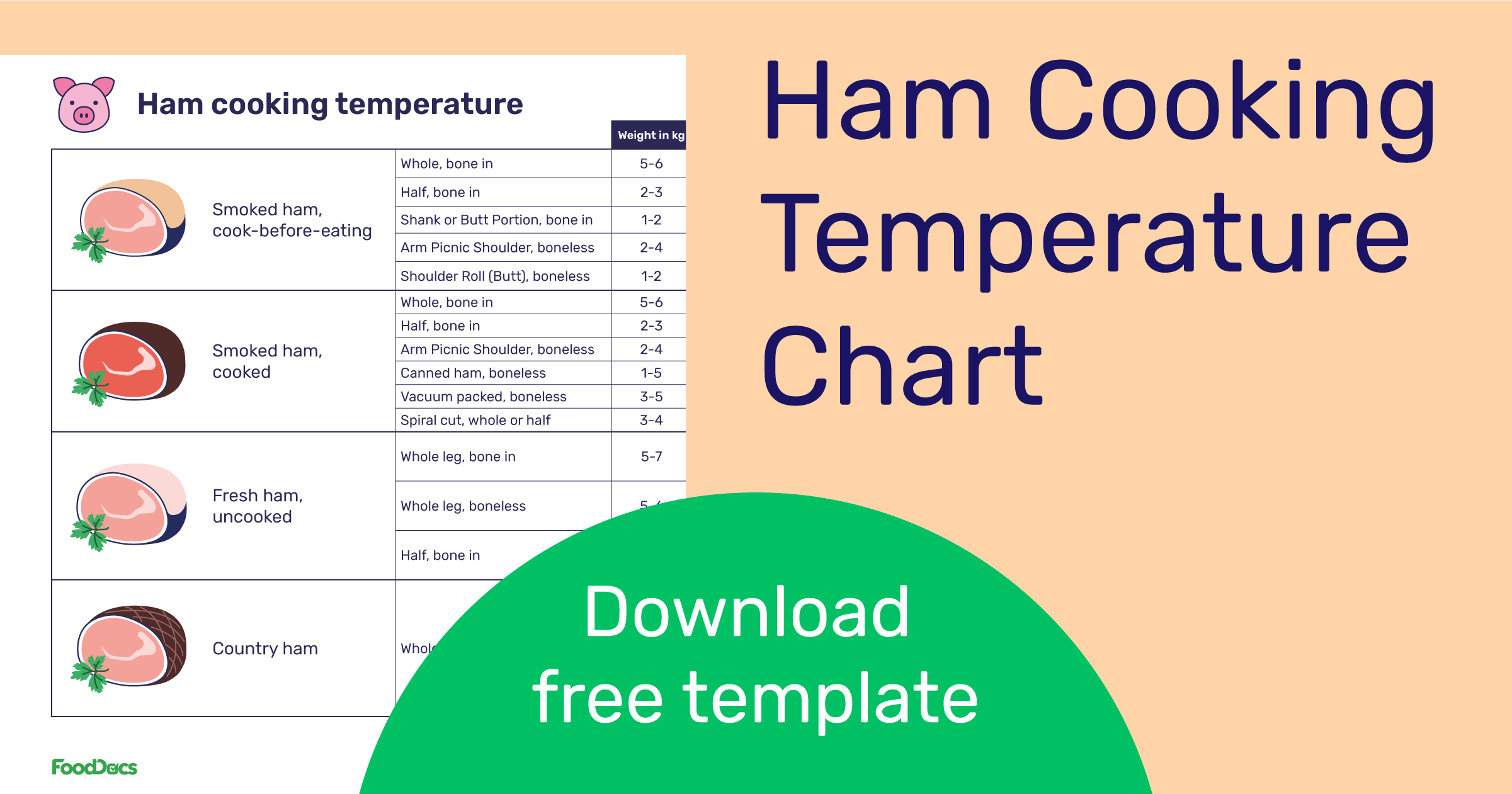

Cooking ham seems straightforward – just pop it in the oven and roast until done. But achieving the ideal internal temperature is key for both food safety and the best texture Follow this guide to learn the right cooking temperatures for different types of ham.

Why Ham Temperature Matters

Cooking ham to the proper internal temperature accomplishes two important things

-

Food Safety – Heating ham to the right internal temperature kills potentially harmful bacteria that could cause foodborne illness. This is especially important for fresh, uncooked ham.

-

Texture – Each type of ham has an ideal finished temperature for optimum moisture and tenderness. Going above or below that range can make the ham dry or undercooked.

So monitoring temperature ensures you safely achieve the best texture and doneness Visual signs like color are not reliable indicators Use a food thermometer to be sure,

Oven Roasting Temperature

While the interior temperature of the ham matters most, the oven temperature does impact the cooking time. Here are ideal oven temps:

-

Whole bone-in ham – 325°F is ideal, allowing the interior to come up to temp before exterior overcooks

-

Half bone-in ham – 325°F to 350°F works well

-

Boneless ham – 325°F to 375°F is good, since they cook faster with less bone

Cook times vary based on size. Smaller hams may need higher oven temps while larger hams do better at lower temps.

Minimum Safe Internal Temperatures

The USDA provides these guidelines for safe minimum internal temperatures when cooking ham:

-

Fresh ham, raw – Cook to at least 160°F

-

Pre-cooked ham, to reheat – Heat to 140°F

-

Ground ham, sausage – Needs to reach 160°F

Always verify temperature using a food thermometer placed in the thickest part of the meat, without touching the bone.

Ideal Internal Temperatures for Best Texture

For the most tender, juicy ham that isn’t dry, follow these target internal temperatures:

-

Bone-in cooked ham – 125-130°F is ideal

-

Boneless cooked ham – 130-140°F is best

-

Fresh bone-in ham – 160°F minimum for food safety

-

Fresh boneless ham – 145-150°F for optimal texture

The benefit of starting fully cooked ham is you don’t need to worry about hitting as high of a temperature. Lower temperatures result in more moist, delicate meat when reheating.

What If Ham Temperature Is Too High or Low?

If undercooked: Place ham back in oven and roast until safe minimum temperature is reached.

If overcooked: Glaze and roast at high heat briefly to restore some moisture and flavor. But overcooked meat will be drier.

Using a thermometer prevents both issues so aim to take temperature frequently.

How Long to Cook Different Types of Ham

Cooking times vary based on multiple factors like ham size, bone-in or boneless, and fresh vs pre-cooked.

Here are general time ranges:

-

Whole bone-in (12-16 lbs) – 18-24 minutes per lb at 325°F

-

Half bone-in (5-8 lbs) – 35-40 minutes per lb at 325°F

-

Boneless (3-6 lbs) – 10-18 minutes per lb at 325°F

-

Fresh – Increase times above by about 5 minutes per lb

The only way to guarantee safety and perfect doneness is using a thermometer. But these estimates provide a helpful starting point.

Tips for Roasting Ham

Follow these tips in addition to the proper internal temperature:

-

Let the ham rest for 10-15 minutes before slicing to allow juices to absorb.

-

Use the oven broiler at the very end if the ham needs more browning.

-

Glaze during last 30 minutes only or it may burn.

-

Cook fat side up to self baste. Tent with foil to prevent overcooking.

-

Cook at lower temps for larger hams and higher temps for smaller hams.

-

Bone-in hams take longer than boneless. Fresh hams take longer than cooked.

Common Ham Cooking FAQs

What if my fresh ham has a USDA safe handling instructions sticker?

Follow the recommended minimum internal temperature and cooking times on the sticker for safety.

Can I eat pink fresh ham like pork?

No, fresh uncured ham needs to reach 160°F minimum for food safety even if it looks pink.

What if my ham comes with reheating instructions?

It’s fine to follow package instructions but still verify temperature with a thermometer.

What if I’m reheating a fully cooked ham?

Heat to 140°F minimum, but 125-130°F will provide the ideal texture.

Can I cook ham from frozen?

Yes, just increase cooking time. Thaw first for shortest cook time.

How do I know when my ham is done without a thermometer?

Using a thermometer is the only way to reliably determine doneness and safety. Never rely solely on visual cues.

Achieve Ham Perfection

From properly reheating pre-cooked ham to roasting fresh raw ham, use a meat thermometer to guarantee your ham reaches the ideal finished internal temperature. This ensures both food safety and the best juicy, tender texture your ham can offer.

Call Our Hotline For help with meat, poultry, and egg products, call the toll-free USDA Meat and Poultry Hotline:

Hams: They can be fresh, cook-before-eating, cooked, picnic and country types. There are so many kinds, and their storage times and cooking times can be quite confusing. This background information serves to carve up the facts and make them easier to understand.

Hams may be fresh, cured or cured-and-smoked. Ham is the cured leg of pork. Fresh ham is an uncured leg of pork. There will be the word “fresh” in the name of fresh ham, which means that it has not been cured. “Turkey” ham is a ready-to-eat product made from cured thigh meat of turkey. The term “turkey ham” is always followed by the statement “cured turkey thigh meat. “.

Cursed ham is usually a deep rose or pink color. Fresh ham, which isn’t cured, is the color of a fresh pork roast, which is pale pink or beige. Country hams and prosciutto, which are dry-cured, are pink to mahogany.

Hams are either ready-to-eat or not. Ready-to-eat hams include prosciutto and cooked hams; they can be eaten right out of the package. People must cook fresh hams and hams that have only been treated to destroy trichinae (this could mean heating, freezing, or curing in the processing plant) before they can eat them. Hams that must be cooked will bear cooking instructions and safe handling instructions.

If a ham isn’t ready to eat but looks like it is, it will have a big message on the main display panel (label) saying that it needs to be cooked, examples g. , “cook thoroughly. ” In addition, the label must bear cooking directions.

Sodium or potassium nitrate (or saltpeter), nitrites, and sometimes sugar, seasonings, phosphates, and cure accelerators are added to make something cure. g. , sodium ascorbate, to pork for preservation, color development and flavor enhancement.

Nitrate and nitrite contribute to the characteristic cured flavor and reddish-pink color of cured pork. Clostridium botulinum is a deadly microorganism that can grow in foods in some situations. Nitrite and salt stop it from growing.

Pork can be injected with flavoring and curing solutions or massaged and tumbling the solutions into the muscle. Both methods make the pork more tender.

For dry curing, which is how country hams and prosciutto are made, fresh ham is rubbed with a dry-cure mix of salt and other things. Dry curing produces a salty product. In 1992, U. S. The USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) approved a trichinae treatment method that lets potassium chloride be used instead of up to half of the sodium chloride. This lowers the amount of sodium in the food. Since dry curing takes away the moisture, the weight of the ham is reduced by at least 20%, but usually by up to 25%. This makes the flavor more concentrated.

Dry-cured hams may be aged more than a year. Six months is the traditional process but may be shortened according to aging temperature.

These hams that haven’t been cooked can be kept at room temperature without getting spoiled by bacteria because they don’t have much water in them. Dry-cured ham is not injected with a curing solution or soaked in a curing solution to make it, but it can be smoked. Today, dry-cured hams may be sold as items that need to be prepared by the customer before they are safe to eat. Just like with any other meat, it’s important to read the label on a ham to see how it should be cooked.

Brine curing is the most popular way to produce hams. It is a wet cure whereby fresh meat is injected with a curing solution before cooking. Salt, sugar, sodium nitrite, sodium nitrate, sodium erythorbate, sodium phosphate, potassium chloride, water, and flavorings are some of the things that can be used for brining. Smoke flavoring (liquid smoke) may also be injected with brine solution. Cooking may occur during this process.

Smoking and Smoke Flavoring

After curing, some hams are smoked. When ham is smoked, it is hung in a smokehouse and allowed to soak up smoke from smoldering fires. This gives the meat more flavor and color and slows down the rancidity process. Not all smoked meat is smoked from smoldering fires. A popular process is to heat the ham in a smokehouse and generate smoke from atomized smoke flavor.

Pathogens that can make you sick can be found in pork, as well as other meats and poultry. These are Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Staphylococcus aureus, and Listeria monocytogenes. They are all destroyed by proper handling and thorough cooking to an internal temperature of 160°F. The following pathogens are associated with ham:

- The trichinella spiralis family includes parasites that can be found on hogs. To kill trichinae, all hams must be processed according to USDA rules.

- Staphylococcus aureus (staph): These bacteria are killed by heat and processing, but they can come back if they are handled incorrectly. Then they can make a poison that can’t be killed by cooking it any further. Dry curing of hams may or may not destroy S. auxreus, but the high salt content on the outside stops these bacteria from growing. When the ham is cut into slices, the moister inside will make it easier for staphylococcus to grow. Thus, sliced dry-cured hams must be refrigerated.

- Mold — Can often be found on country cured ham. Most of these are safe, but some molds can make mycotoxins. Molds grow on hams during the long process of curing and drying them because the high salt and low temperatures don’t bother these tough organisms. DO NOT DISCARD the ham. Use hot water to clean it and a stiff vegetable brush to get rid of the mold.

When buying a ham, figure out what size you need by looking at how many servings that type of ham should make:

- 1/4-1/3 lb. per serving of boneless ham

- 1/3-1/2 lb. of meat per serving of bone-in ham